“Helen, daughter of Zeus, took other counsel. Straightway she cast into the wine of which they were drinking a drug to quiet all pain and strife, and bring forgetfulness of every ill. Whoso should drink this down, when it is mingled in the bowl, would not in the course of that day let a tear fall down over his cheeks, no, not though his mother and father should lie there dead, or though before his face men should slay with the sword his brother or dear son, and his own eyes beheld it.”

Homer, The Odyssey

Even for Star Trek: Picard, “Nepenthe” is an amazing episode. Written by Samantha Humphrey and the show runner Michael Chabon, it is so beautiful, so emotional, so rich and subtle and layered, that for a long time I wasn’t sure how to write about it. Watching it again very recently, I was filled with so many thoughts, and so aware of myriad layers & connections, that I’m glad I’d already written down many of them in the year that I’ve been thinking about the episode. Like Picard Season 1 as a whole, it benefits from rewatches, because with its unhurried pace it contains so much. It’s a joy to see the actors given such a gift, and playing their hearts out on screen. The performances by Stewart, Sirtis, Frakes, Briones and the young Lulu Wilson as Kestra, are a deep, natural, joyous delight. And, as with some other episodes in the season, things that seemed jarring or out of place on a first watch now seem smoothed out, to find their place in the whole.

At this point in the season’s narrative, which reached an almost unbearable pitch of tension at the end of the previous episode, we as viewers need a point of rest - for Picard and Soji, anyway. And on the planet Nepenthe, they find it! All is not perfectly calm and resolved here; as Deanna says, Soji is traumatised. But it gives them both a chance to catch their breath, be surrounded by love and trust, and gain a sense of stability. And for us as viewers, thrown into a series that’s very different from the TNG of three decades ago, that stability comes partly from the sudden sense of familiarity. There’s nostalgia here (in the best sense), a nostalgia achieved partly by harking back to a specific TNG episode. And it’s beautiful.

This is one of the most immediately striking things about “Nepenthe” - that it’s a clear riff on “Family”, in which Picard returned to Earth and his family home to recover from the trauma of his assimilation by the Borg. That was in itself a nostalgic episode, of course; the Picard vineyard represented an older, simpler, less dangerous way of life, the scene of Picard’s childhood. And that same vineyard is where we found him at the beginning of this new series - except that he couldn’t find true peace there, not permanently. Picard belongs in space, with a mission. But in “Nepenthe” he finds a blessed moment of calm with Will and Deanna, part of his “found family” and the only one he was ever really happy with.

Here are some of the episode’s parallels and references to “Family”, some of them so specific that it can’t be coincidental.

Picard goes to a rural, safe place after escaping from a Borg cube, and is immediately accosted by a beautiful blonde child. In “Family” he raises his hands and says, “oh good lord, a highwayman!” Nepenthe is just a little darker; after he and Soji raise their hands Picard asks, “are we safe here, Kestra?”

Picard and the child walk along a quiet country path. In “Nepenthe” it’s actually Kestra and Soji who walk together, while Picard hangs back a little. Again, the mood and conversation are more serious this time.

The child runs ahead and calls to their parents that Picard has arrived. In both cases, it’s the mother who is first to greet Picard. (Especially in the context of this season, Marina Sirtis’ wonderful acting here is indescribably moving.)

Both episodes are preoccupied with food and drink! - in both the A and B stories. In both episodes, the food on the planet is home-grown, home-cooked, “real”, while the food on the ship is replicated. Soji bites into her first real tomato, while Auntie Raffi (who takes the place of Guinan here) makes the red velvet layer cake materialise as if in a transporter beam.

A family dinner scene, and a later one where Picard drinks wine with the father/husband. Although not completely free of tension, both of the Nepenthe scenes are far less awkward, far warmer than their counterparts in “Family”, because Picard is with his true, found family rather than his family of origin.

A big, deeply felt embrace at the end, followed by a leave taking. Picard feels more at peace, with a renewed sense of confidence and direction.

These parallels and call backs are very moving; as with other stories in the new era of Star Trek, both episodes somehow enhance each other. But what of the deeper themes of the episode? “Family” explores some darker undercurrents beneath the idyll, but “Nepenthe” goes further, and the “B” and “C” stories are remarkably more troubled than the earlier episode’s. So much so that they stand in an uncomfortable contrast to the beautiful scenes on the planet. The La Sirena story is more troubled than the planet bound one, while the scenes on the Artifact are violent and upsetting. Hugh sees his own found family massacred by Narissa, before we (who care about Hugh as another legacy character) see him murdered in his turn. This was a development that upset many fans, and it’s such a sharp, unexpected contrast that for a long time I too saw it as an unnecessary blot on an otherwise perfect episode. Why Hugh? Why this character we had really only just got to know, yet already come to love? It all felt a bit senseless.

Now I’m not so sure. Beneath the episode’s sharp contrasts, there are deep underlying themes common to all the three stories. Like “Family” but even more so, “Nepenthe” is not the perfect idyll it may superficially seem, even down on the planet. The clue is in the title, after all. Nepenthe is a drink or potion mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey, with the power to make one forget sorrow. And despite the abundance of love and trust between the three main legacy characters, there is plenty of sorrow in this wonderful but far from carefree episode. Perhaps more than anything else, “Nepenthe” is an episode about grief and the assuaging of grief.

One of the main themes of Picard Season 1 is that of grieving, remembrance and learning to live with loss, not through anaesthetising or dissociating but through openness, trust and connection with others. This applies both in the wider political story and on the deeply personal level experienced primarily by Picard, but also the rest of the crew of La Sirena, all semi-broken in their different ways. Each learns this lesson gradually, and in the episode that follows “Nepenthe”, the broken pieces of the story and the crew finally come together. La Sirena starts to become a classic Star Trek “found family”. So it’s appropriate that a turning point in the season comes when Picard returns to a part of his own found family, Deanna and Will. The Troi-Rikers are not immune to grief and have not escaped it, but they can cope with it and at the same time love the life they have together, because they love and trust each other.

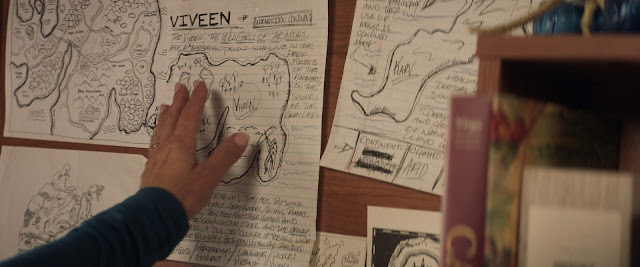

The sense of stability that this brings is expressed in part by the season’s recurring theme of home and homeworlds. The Romulan people have lost their homeworld, destroyed by the supernova, and now live as barely tolerated refugees. The XBs were wrenched away from their homes the moment they were assimilated, and are feared and hated outcasts. Soji and Dahj both came to the horrified realisation that their “homes” were pure illusion, and Soji is now trying to find her true homeworld before the Zhat Vash do. Picard returned “home” fourteen years ago, but ironically never felt at home there, because he’d always looked to the stars and besides, didn’t feel at home in himself. And Thaddeus Troi-Riker, who grew up on a starship, was fascinated by the idea of homeworlds and created imaginary ones, with maps and invented languages that he shared with his sister. (This is very moving and, if I may say so, typically Michael Chabon!) Even now, years after Thad’s death, Kestra plays out some of those stories on what has become her own homeworld, the idyllic planet of Nepenthe. Riker may be on active reserve with Starfleet, but he and Deanna have chosen to remain on Nepenthe, providing a sense of peace, beauty and stability for their daughter to grow up in.

The crew of La Sirena have no such home, and very little stability, but “Nepenthe” is a turning point for them as well as Picard and Soji. Although Raffi’s attempts to soothe Agnes are ultimately ineffective (and very Raffi, in that she’s using food as a drug), her motherliness shows the beginnings of a sense of family on the ship. And Agnes’ response, though drastic, shows that this growing feeling (still mixed with some distrust on Rios’ part) is affecting her in positive ways. Exhausted by her constant deception, her inability to be her own self with people who care about her, Agnes finally decides to trust the others and get rid of the viridium tracker in her body. So, for a brief while, cake may have seemed to be the answer (the drug that induces forgetfulness), but love does manage to get through. And things begin to change.

Agnes may now be in a coma, but in the following episode she awakes, and shares her grief, fear and guilt with Picard. Yes, grief is an overwhelming part of her experience too. The planet she saw in the Admonition, the tumult of traumatic images she received through Oh’s mind meld, is Aia, the Grief World. This we see in the cold open of “Nepenthe”, though we only learn its name later. Agnes is living a grief that no one can truly comprehend, the loss of all organic sentient life, partly (she believes) through her own role in helping to create synthetic life. This burden is overwhelming, and she cannot bear it anymore. So she takes a decision that may kill her (which would be one form of escape, the ultimate anaesthetic), but ultimately allows her to share her burden with her found family. Picard, Raffi, Rios and Elnor- the only family she appears to have.

This is consistent with another theme of the episode, the question of “real versus unreal”. Agnes has been living a whopping great lie since she arrived on board: her true reason for being there, her murder of Bruce Maddox, her reluctant mission to end synthetic life, not save it. It’s her growing sense of trust and connectedness with her found family that allows her to stop lying and reveal the truth. Lying and deception are a huge theme of the season, on both political and personal levels, and they are based ultimately on fear of annihilation. But as Picard says to Rios at the end of “Broken Pieces”, “They may be right about what happened 200,000 years ago. The past is written, but the future is left for us to write, and we have powerful tools, Rios: openness, optimism, and the spirit of curiosity. All they have is secrecy, and fear, and fear is the great destroyer, Rios.” , “They may be right about what happened 200,000 years And so, Agnes gives up deception and is “real” for the first time. Her found family, however flawed and as yet half-formed, allows her to do this.

Similarly on Nepenthe itself. Soji has also been living a lie, without knowing it this time; everything she remembers of her life has been implanted false memories. She’s not even human; Narek told her she wasn’t “real”. Again, the grief such a sense of loss must bring is something we can’t completely comprehend, since it can only happen in science fiction (although it’s also a metaphor for the gaslighting, othering and dehumanisation in our real world). Soji now questions reality itself, since anything she experiences may be just another illusion. “Just get on with the mind games”, she tells Picard bitterly. As Deanna chides Picard with unforgettable emphasis, “her capacity for trust was a flaw in her programming.”

Fortunately, Soji has now fallen in with people who know all about what’s “real”. It’s not just the delicious tomatoes, the home-cooked pizza, the basil that “grows like weeds” in the planet’s regenerative soil. Riker and Troi knew Data, the android who wanted to be human. And they loved him, clearly. Kestra, who was born after Data’s death, is fascinated by him, not just his extraordinary abilities but also that “all he ever really wanted to do was have dreams and tell jokes and learn how to ballroom dance.” Kestra can only know these things because her parents told her so many stories about Data - which shows how deeply they knew and loved him. Riker even recognises Soji as somehow “related” to Data, simply by her curious head tilt (a wonderful moment by Briones!) Data, whose memory has haunted Picard for twenty years, is very present in this episode, as indeed is his daughter Lal, who was in a sense the half sister of Dahj and Soji.

Riker and Troi know that Data was real, even if he wasn’t biologically human. His self awareness, his selflessness, his desire to procreate and to make art, to contribute to society, his capacity to mourn dead friends (in his way), to love and be loved, are what made him a real person. This is the constant background “message” of Picard Season 1, and arguably of Star Trek as a whole: that we are all of equal value (“everybody’s human”, as Kirk goodnaturedly insults Spock by saying). You can be a Romulan, a human, an ex-Borg or a “synth”, and it doesn’t matter either way. We’re all real. “Romulan lives”, comments the unconsciously racist reporter. “No, lives!” insists Picard, his moral compass undamaged even by the mistakes and traumata of the past fifteen years.

In “Dark Page”, another TNG episode recalled by “Nepenthe”, Deanna had tried to help her mother uncover true memories, in order to save her life. Now, she helps Soji to deal with the fact that her memories are false, so that she can start a new life. And to know that regardless of whether she was made or born, she’s still real and her life is real too. This pure Star Trek idea is taken to its ultimate conclusion in the season finale, when Picard is briefly reunited with his friend Data, then has his own consciousness downloaded into a synthetic body, while remaining absolutely himself in every way. Picard is still Picard. Data was human. Picard is an android. Both of them as real as anyone, any life, can be!

The abundance of love and trust on Nepenthe (even the slightly cranky-sounding Captain Crandall is trusted as Kestra’s friend!) is what allows Deanna, Will and Kestra to live happy lives, despite their shared sorrow. Grief is far from absent on Nepenthe - though it might be forgotten for a little while, in the presence of nature, laughter, family. And it can’t be banished by red velvet layer cake and bunnicorn pizza alone! But love, trust, and openness, a connection with those we most love, can make it bearable. For me, the defining image of “Nepenthe”, the one that comes immediately to mind when I think of the episode, is the one at the head of this article. Love soothes all pain, even if it can’t actually cure it.

So grief and sorrow remain. And recognising that, the upsetting scenes on the Artifact - Hugh’s death included - now make sense to me. Why does Hugh’s murder upset us so much more than that of a character we’ve never met? Precisely because we know him and care about him. (“Or though before his face men should slay with the sword his brother or dear son…”) Why is the murder of his fellow XBs so distressing to watch? Because we see Hugh’s traumatised, distressed, grief stricken reaction - so we feel his grief. It was no different for the Troi-Rikers when Thad died; he was their family, so they grieved for him. Where there’s love there’s potential grief; it runs the risk, even the likelihood, of sorrow. Grief is the price of living, just as death is. The question both asked and answered in “Nepenthe” is, how do we deal with this?

In the fourteen years leading up to “Remembrance”, Picard had tried to escape from painful regrets by retreating to rural France, dissociating from his feelings, his friends and from his long, fulfilling former life in Starfleet. But as he recognised in that first episode, “I haven’t been living. I’ve been waiting to die.” Recognising this is Picard’s first step towards a new life. He has to face and admit to other regrets as the season progresses, including the cost of his withdrawal on Raffi, Elnor and the Romulan refugees. But his epiphany in “Remembrance” is the start of his adventure.

In “Dark Page”, Lwaxana Troi had tried to bury grief, by repressing all memory of her deceased daughter Kestra - but the psychological pressure of forcing such a traumatic event out of her consciousness was killing her - until Deanna helped her to face it and ultimately celebrate Kestra’s life. Now a bereaved mother herself, Deanna has one child dead and one child living, just like her mother. But unlike Lwaxana, she allows herself to feel the grief, however painful. She knows that with the help of her husband and daughter, their shared grief and love, she can live with it and celebrate Thad’s remarkable life. Just as she’d celebrated her sister’s life by naming her own daughter after her.

And so… Deanna and Will lose their son, and Kestra loses her brother. Hugh loses his found family, and then his own life, and we as viewers with our own feelings lose Hugh. Agnes and Soji lose their sense of reality; everything they’d thought was real is wrenched away from them, leaving no sure ground to stand on. Loss, grief, death, sorrow… all these things are an inevitable part of life. How do we live with that? With fear and distrust? By hiding from the world and our friends, our “family”, as Picard was doing in “Remembrance”?

It’s a testament to the writing, direction and intensely warm and “real” performances that despite the grief and occasional horror in this episode, most people’s dominant impression seems to be of love and beauty and warmth. “Nepenthe” is like a soft warm blanket to snuggle up in. And perhaps, after all, love and trust *is* the drug that brings forgetfulness of sorrow. Deanna tells Picard that Kestra’s ache for Thad is gradually fading, and Kestra tells Soji that a bad thing happened to her but her parents helped her through it. We can accept mortality, however painful, and still enjoy the life that we have while we have it - because we have each other.

To quote “The Faerie Queene”, written by Edmund Spenser in 1596:

Nepenthe is a drink of sovereign Grace,

Devised by the Gods, for to assuage

Heart's grief,

and bitter gall away to chase,

Which stirs up anguish and contentious rage:

Instead thereof, sweet peace and quiet age

It doth establish in the troubled mind.

Few men, but such as sober are and sage,

Are by the Gods to drink thereof assigned;

But such as drink, eternal happiness do find.

And in his own way, perhaps Data says it too, right at the end of this first season of Picard, when he meets his friend and former captain in the quantum simulation and asks him to terminate his consciousness:

“I want to live, however briefly, knowing that my life is finite. Mortality gives meaning to human life, Captain. Peace, love, friendship, these are precious, because we know they cannot endure.”

As so often in Star Trek, Data is as wise and human and real as anyone!

No comments:

Post a Comment